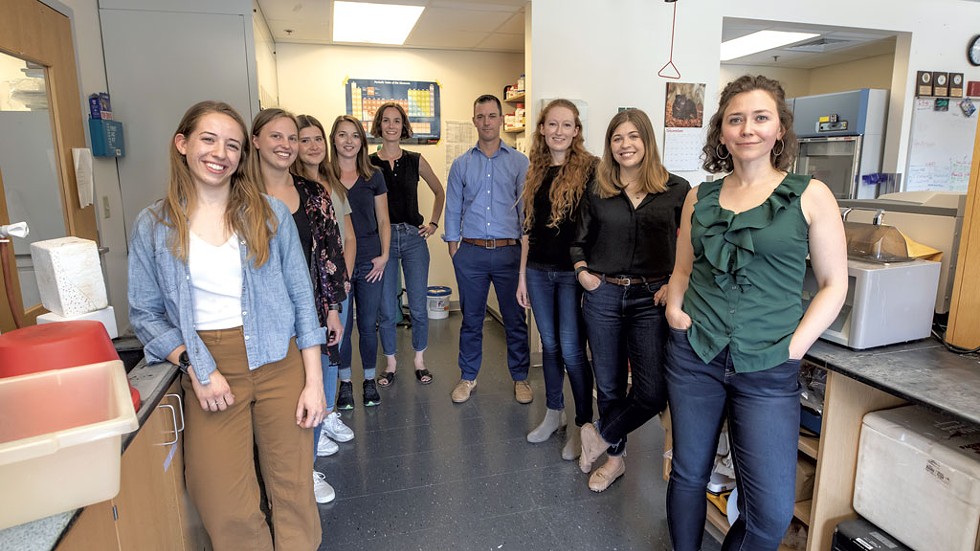

From left: Sarah Vandal; Katie Queen; Hannah Poquette; Katie Schutt, PhD; Alex Thompson; Jason Stumpff, PhD; Carolyn Marquis; Leslie Sepaniac; and Cindy Fonseca, MS

Significant advances in the fight against cancer aren't always made by a single inspired scientist; often they're accomplished by a team. The University of Vermont Cancer Center excels at supporting and promoting team science. Sometimes, those teams even include undergraduate students at UVM.

During their time at "Groovy UV," alumnae Lisa Wood, '18, and Carolyn Marquis, '19, contributed to foundational scientific research that could someday lead to new ways of fighting triple negative breast cancer. Both worked in a molecular physiology and biophysics lab run by UVM Larner College of Medicine associate professor Dr. Jason Stumpff. He's one of more than 210 members of the Cancer Center.

Wood and Marquis began working in Stumpff's lab during the summer after their sophomore years through the Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship. It gives students the chance to be part of a real-world lab outside of a classroom setting.

The experience was pivotal for both women. They had the opportunity to publish their findings in Nature Communications last February; Marquis was named as the article's first author.

"First author identifies the investigator who really drove the project," Stumpff explains in a March article on the UVM website. It's an unusual accomplishment for a student without an advanced degree. "Carolyn also completed important experiments for a related project that was published in Nature Communications a few weeks ago. She is a coauthor on that study, which was a collaboration between six labs in five different countries."

A new path for treatment?

Lisa Wood - Courtesy of Lisa Wood, Cindy Fonseca, and Carolyn Marquis

Lisa Wood - Courtesy of Lisa Wood, Cindy Fonseca, and Carolyn Marquis

Breast cancer is the second most common cancer in women. There are multiple types, each requiring a different treatment. Triple negative breast cancer, a rare and aggressive form of the disease, doesn't respond to many treatments. Chemotherapy is effective against it but kills healthy cells, as well. Currently there aren't many other options.

To develop new therapies, drug companies rely on researchers such as Stumpff and his colleagues to identify approaches that might work.

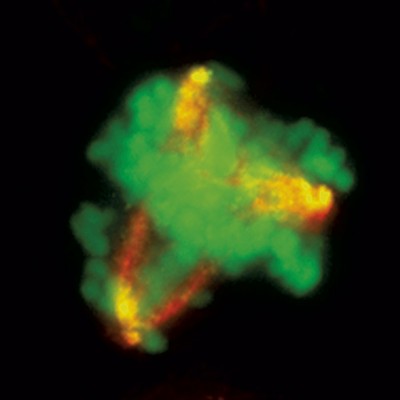

For the last couple of decades, Stumpff has concentrated on understanding how cells divide. The research in which Wood and Marquis were involved focused specifically on a cell protein called KIF18A. The lab was able to show that this protein plays a larger role in the growth of triple negative breast cancer and colorectal cancer cells than it does in the growth of normal cells. In other words, that protein could be a new path for treatment.

Observations made by Wood and Cindy Fonseca, a senior technician, led the lab to further investigate KIF18A. Stumpff says that, when they see initial evidence of a "high-risk, high-reward" finding — one that might not turn out to be significant — they'll often have a student look into it further. "If it doesn't pan out, the student still gets the benefit of having done research," he says.

That happens frequently. "There are a lot of days when things just don't work," Stumpff notes.

But the protein discovery did — and it ended up providing Wood and Marquis with a basis for their honors theses. The research gave both undergraduates an opportunity to work with international collaborators, as well as a lab team that included a graduate student, a post-doc fellow, a senior technician, an oncologist, scientists from Vermont-based medical instrument company BioTek and two patient advocates — both breast cancer survivors with scientific backgrounds.

"Receiving feedback from these individuals gave me a broader perspective on the project," Marquis says, "and it reinforced that the work we do in the lab has real potential to help people."

'It opened my eyes'

Carolyn Marquis and Dr. Jason Stumpff - Photograph by Luke Awtry

Carolyn Marquis and Dr. Jason Stumpff - Photograph by Luke Awtry

A desire to help patients is what first drew Marquis to this work. When she was 8, her grandfather was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. The doctors gave him eight weeks to live. "I didn't really understand why they couldn't do anything," she remembers.

That experience planted a seed; years later, the Nashua, N.H., native came to UVM to pursue medicine. When she got her job in Stumpff's lab, Marquis remembers following technician Fonseca around and asking questions. And suddenly, things clicked into place. "I remember just thinking, 'This is it. This would be a really cool way to be involved,'" she says.

After graduation, Marquis delayed applying to medical school and went to work full time in Stumpff's lab to see her project through to completion. She's now applying to schools for admission in the fall of 2022.

For Wood, working in the lab actually helped her decide not to go to med school. When she was growing up, the Cancer Center was a big part of her life: Her mother, Dr. Marie Wood, is an oncologist there. Lisa sometimes came to work with her mom and saw how doctors fought to prolong their patient's lives.

Though she had planned to follow her mom into oncology, Wood changed her mind after working in Stumpff's lab. Observing the science behind the development of cancer treatments appealed to her, she says. "It definitely opened my eyes to what the options are." Wood is now pursuing a PhD at the University of Colorado Anschutz School of Medicine and believes her lab experience was key to her acceptance in the program.

Coincidentally, Marie Wood and Stumpff shared office space when he first arrived at UVM in 2011. They purchased a coffee machine together to encourage the clinical staff and foundational scientists to congregate and get to know each other, Stumpff says. Efforts like those illustrate the Cancer Center's collaborative "from bench to bedside" approach.

'Passionate about what they do'

A triple negative breast cancer cell - Courtesy of Lisa Wood, Cindy Fonseca and Carolyn Marquis

A triple negative breast cancer cell - Courtesy of Lisa Wood, Cindy Fonseca and Carolyn Marquis

Stumpff says mentoring students such as Marquis and Wood and training the next generation of researchers is one of the most rewarding things about his job. The first undergraduate he worked with at UVM just completed medical school and is doing a residency in emergency medicine at Dartmouth-Hitchcock medical center.

When Stumpff was a biology major at Eckerd College in Florida, he assisted an orthopaedic surgeon for a time. He also worked as a vet tech rescuing dolphins and helping baby sea turtles find their way to the ocean. Between his junior and senior years, Stumpff worked in a lab at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

He says he paid attention to all the various people he worked with over the years, noticing how happy they seemed to be in their jobs. "No one was quite as excited to go to work every day as the people who worked in the lab," Stumpff recalls.

Marquis says she sees the same drive at UVM. "Everyone I've worked with in our lab is really passionate about what they do. The energy level is really great," she observes. "I think that makes a difference when the people who you work with love what they do."

Cancer Center Offers Access to Breast Cancer Clinical Trials

In addition to the ground-breaking scientific research taking place in Dr. Jason Stumpff's lab, multiple clinical trials through the UVM Cancer Center are evaluating new and promising breast cancer treatments.

Dr. Peter Kaufman, an oncologist, describes two of the trials as "very exciting, world-class research": a Phase 3 trial treating advanced metastatic breast cancer with a new drug combination — a large international clinical trial evaluating the widely used chemotherapy eribulin, but in combination with an exciting novel biological medication called balixafortide — and a study funded by Lilly Pharmaceuticals testing a new class of hormonal therapies known as selective estrogen receptor degraders, aka SERDs. Several UVM patients are already enrolled in both of these studies.

"These trials are providing cutting-edge therapies to patients that are looking very promising, that they wouldn't otherwise be able to access," Kaufman says.

He and his colleagues are in fact reporting the first results from the Phase I SERD trial at the annual American Society of Clinical Oncology meeting this week.

This research means that Vermont breast cancer patients don't need to travel to Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston or Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York to access top-notch treatment. They can find it here at home.

Says Kaufman: "We're all very proud of the quality of care, and the state-of-the-art level of care that our patients are able to receive here at the UVM Cancer Center."

About this series:

The University of Vermont Cancer Center in Burlington brings together research, medical education and state-of-the-art patient care, giving patients their best possible chance for survival. This 7D Brand Studio series, commissioned and paid for by Pomerleau Real Estate, explores some of the ways in which this extraordinary local resource benefits our community. Community donations support the exceptional research, education and care at the UVM Cancer Center. Please contact Lindsay at lindsay.longe@uvmhealth.org for information.

This article was commissioned and paid for by Pomerleau Real Estate.

Read full story

at

Seven Days