The University of Vermont’s medical and nursing curriculum will be delving into more progressive territory, courtesy of five new Frymoyer Scholars projects.

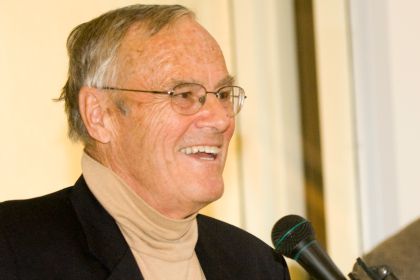

John Frymoyer, M.D., former dean of the UVM College of Medicine from 1991 to 1999 and CEO of the former Fletcher Allen Health Care, now UVM Medical Center, from 1995 to 1997. (Photo: COM Design & Photography)

The University of Vermont’s medical and nursing curriculum will be delving into more progressive territory, courtesy of five new Frymoyer Scholars projects. The selected projects, which were announced in May, will focus on interprofessional training, specialty clerkships in rural healthcare and biomedical research, educational modules for LGBT health, and the integration of families in hospital rounds.

Each year, the John W. and Nan P. Frymoyer Fund for Medical Education provides financial support for physicians, nurses and others in the healthcare field who propose enhancements to medical and nursing student learning and exhibit leadership as clinician-teachers, with an emphasis on patient care. Several faculty members in the UVM College of Medicine and College of Nursing and Health Sciences have received awards this year for their proposed projects on new approaches to traditional modes of medical education.

Engaging Patient Families in Hospital Rounds

Traditionally, patients and their families have taken secondary roles in the process of hospital rounds, says Karen Leonard, M.D., UVM associate professor of pediatrics. Medical students present patient cases to residents and attending physicians with a heavy dose of medical jargon, while family members stand on the sidelines.

“And the family turns to the nurse and says, ‘What’s happening?’ ” Leonard says. “What we really were doing was talking and translating.”

At the University of Vermont Children’s Hospital, Leonard has worked with nurses, residents, doctors and family advisors to develop the Family Centered Rounding Model. It emphasizes collaboration between healthcare providers and patients and their families and inclusion of and respect for families in all aspects of communication and care.

The model starts with a family meeting, when a medical student finds out the family’s chief concerns and sets the rounds agenda around them. The family might want to discuss medication or a change in the patient’s appetite, so that becomes the focal point of the presentation.

“We want the family’s questions answered,” Leonard says.

The challenge with the family-centered model is the players change frequently, Leonard says. Medical students and residents rotate through, nurses have varying shifts, and other participants – who can include child life specialists or pharmacists, depending on the patient’s needs – come and go.

Leonard proposes to address this with two avenues of training: an online module and simulation exercises. The online portion includes a video that depicts both a traditional rounds scenario and family-centered rounds. The simulation training uses the Standardized Patient structure, which Leonard has already used for residents with much success, she says.

When medical students begin their rotations, they learn “a new vocabulary of medicine” to communicate the information they have absorbed in classrooms to their medical peers, and this initiative would enhance those verbal skills, Leonard says. It could provide valuable training for all physicians who interact with families throughout their work, she says.

“You always have to communicate with families, and you always have to do it effectively and compassionately,” Leonard says. “There’s a lot of nuanced experience that you get from this.”

LGBT Health Modules to Enhance Medical Student Education

Modern medical students often have the most progressive – and the savviest – perspectives on patient care. That’s particularly true with UVM College of Medicine students in addressing the healthcare concerns of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and gender-conforming patients, says Michael Upton, M.D., clinical assistant professor of psychiatry, co-advisor of the College of Medicine’s Gender & Sexuality Alliance, and a member of the Dean’s Committee on Diversity and Inclusion.

“That doesn’t mean that everyone in our teaching community has been exposed to this material,” Upton says. In many cases, “the students are asking us to know about stuff that we were never taught.”

Such information is increasingly important because of the health disparities faced by the LGBT community and particularly LGBT youth, who are at higher risk for mental health problems, substance abuse and violence. Upton has proposed to create a series of educational models focused on LGBT health that students, faculty and others addressing healthcare issues at UVM can access and use for teaching tools, professional training and continuing medical education.

The mostly online presentations would include multimedia, interactive programs and live workshops. In support of the College of Medicine’s shift away from traditional lectures and toward more active learning in classrooms, students and faculty could use the modules to prepare, then apply those lessons during in-class team activities.

“It stays there, and it’s online,” Upton says. “People can go in and take a piece of it for an assignment.”

One module might focus on issues related to men having sex with men. A third-year medical student, for example, recently developed a training program for assessing HIV risk and benefits of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis to prevent infection. Another module could contribute curriculum related to transgender patients. The content will include input from community groups such as the Vermont Pride Center and Outright Vermont.

Increased understanding of health disparities through the lens of the LGBT experience translates to any individuals or groups with unique health concerns that have been overlooked or given limited attention in traditional medical education and practice, Upton says.

“You really can’t understand, for instance, LGBT folks without talking about how to work with people of different racial backgrounds or different cultural backgrounds.”

Rural Health Track Longitudinal Clerkship Pilot

Traditional medical education involves a clerkship year, when students rotate through multiple specialties, each for three to six weeks. At the UVM College of Medicine, some students jump to affiliate sites at medical centers in Danbury, Conn., and Bangor, Maine, for parts of their clerkships. They won’t stay long enough to get to know those communities or those patients, whom they might see only once during that clinical rotation.

“They just start to get confident and good, and then they move on,” says Martha Seagrave, PA-C, R.N., UVM associate professor of family medicine and director of medical student education programs.

She and Felix Hernandez Jr., M.D., director of undergraduate medical education at the College of Medicine’s clinical teaching partner Eastern Maine Medical Center in Bangor, have proposed an alternative that would allow students to complete a full year-long rotation at a single practice in a rural setting. With a longitudinal integrated clerkship in a Rural Health Track pilot, six Class of 2019 students will have an opportunity to spend 12 months in primary care practices affiliated with Eastern Maine Medical Center.

Working under faculty physicians as their mentors, the Rural Track students will follow a panel of patients through the year as they interact with all aspects of the medical system, caring for them both in and out of the hospital setting.

“Students embedded in these medical homes will benefit from better understanding of disease progression as it develops over time and will use a patient-centered approach to dealing with health and illness, which is difficult to achieve in the traditional clerkship model,” Seagrave and Hernandez wrote in their proposal.

Today, more patients rely on outpatient clinics and physician practices for medical care they used to receive at the hospital. Students in the Rural Health Track will get exposed to a range of patient needs.

“You do need to be prepared for a lot,” Seagrave says.

This shift has contributed to an ongoing shortage in primary care physicians, which the Rural Health Track could help address by encouraging students who complete it to return to those communities or similar practices for their careers, Seagrave says.

The longitudinal clerkship isn’t necessarily a better way of teaching than the traditional rotations for every student, Seagrave emphasizes. “It’s just that this is a great option that provides students with an alternative.”

A Biomedical Research Track for Medical and Nursing Students

When Renee Stapleton, M.D., Ph.D., went to medical school, she expected to follow a traditional career path into internal medicine or primary care. Then, she got hooked on clinical research.

That’s how most medical scientists end up in their fields. It depends largely on happenstance – brief exposure to a project or presentation that piques their interest and propels them to pursue a fellowship or graduate program on a research track, says Stapleton, UVM associate professor of pulmonary medicine. Few medical schools teach research within the regular curriculum.

“The skills to do research are completely separate,” she says.

Stapleton and Amy O’Meara, Dr.N.P., UVM clinical assistant professor of nursing, decided that information about research options and methodology should take place earlier in medical training. They have proposed a biomedical research track for medical and nursing students to learn specific skills and find out about potential careers in either laboratory, or bench, research or clinical study of patient treatment and outcomes.

Offered as an elective, the research track would involve a teaching component, as well as hands-on workshops and seminars and a long-term project with a faculty mentor. Stapleton and O’Meara would allow students to jump into the research track at any point in their training, unlike some medical school programs that require students to choose a research focus when they start school.

“We don’t really know what kind of audience it will draw yet,” Stapleton says.

Early exposure to basic science research benefits any medical professional, who should understand methods of data collection, analysis and presentation and apply critical reasoning to studies of literature relevant to their patient care, Stapleton says.

Fewer medical professionals are going into research, partly because federal funding for projects has stagnated since the late 1990s. “The research pipeline is terribly underpopulated at the moment,” Stapleton says, leaving the medical community with a “lack of folks in the workforce who contribute to new generation knowledge.”

An Interprofessional Simulation Curriculum for Burn Care

The UVM Medical Center, a Level 1 Trauma Center serving Vermont and northern New York, is the only facility north of Boston that provides acute burn care and is one of more than 100 facilities nationwide that will accept burn patients.

However, due to a relatively low-volume patient population requiring this specialized care, arranging for clinical training opportunities in burn care management is difficult, and especially challenging for providers who require ongoing training to maintain proficiency in best practices in burn care. Sixty-four burn cases – 90 percent involving second or third-degree burns – were seen by UVM Medical Center providers over the past two years, according to preliminary data.

To address this need, surgical intensive care nurse Patrick Delaney, B.S., R.N., C.C.R.N., and simulation nurse educator Aimee Wilson, B.S.N., R.N., proposed the development of a hands-on, team oriented program that will provide the opportunity for burn care providers to practice standardized skills in a simulated environment and develop best practices for effective teamwork and clinical communication.

Focusing on initial management of the burn patient utilizing scenarios built to include American Burn Association burn center recommendations, the curriculum will include specific cases to meet objectives for each unit involved in a patient’s care. Future outreach may include offerings to pre-hospital ambulance agencies, outlying hospitals in the UVM Health Network, and the American Burn Association’s Advanced Burn Life Support provider course, to contribute to standardization and improved continuity of care for burn patients in the region.

John Frymoyer served as dean of the UVM College of Medicine from 1991 to 1999. During that time, he spent two years as CEO of Fletcher Allen Health Care, now UVM Medical Center. Nan Frymoyer, his late wife, worked as a community health nurse and served on the advisory board of the UVM College of Nursing and Health Sciences. Learn more about The Frymoyer Scholars Program.

(Sara White, communications and student services specialist in the UVM College of Nursing and Health Sciences, contributed to this article.)