Doug Sewall, M.D. ’74

Applying to Medical School

My interview at the University of Vermont College of Medicine in Burlington, Vermont, was scheduled for early January 1970, less than a week after the city had been blanketed with a thirty - inch snowstorm. My mother had called a friend who lived in South Burlington and arranged for me to stay overnight with her the night before my interview. As I drove from Brunswick across New Hampshire the snow banks grew taller and the roads narrower. Near Barre the road became one way only, as a road crew worked with front-end loaders and trucks to remove snow from the other lane. Slowly, I picked my way through the snow and traffic to Montpelier.

Back then Interstate 89 only existed from Montpelier to Burlington; as I started north on I-89 I noticed that there was only one lane going north and one lane going south…and I could not see over the snow banks. It was like driving on a bobsled run. In South Burlington I worked my way through late afternoon traffic and found the home where I was staying for the night, parking my car as best I could, driving the front end up on top of a snow pile next to the garage. The next morning, I threaded my way through traffic on narrowed streets to the beautiful new medical school building. Several applicants were gathered in the Admissions Office; a couple had rescheduled due to weather – related travel delays. The secretary offered us coffee, which tasted awful. I sipped a bit, left most of it and did not complain. Later I wondered if that had been a test that I had failed. After welcoming comments from the Dean of Admissions, we were squired off to separate personal interviews.

I had two interviews with doctors on the medical staff, and both went well. The first was with Dr. Charles Phillips, an expert on viral diseases (including polio) and vaccines, and I enjoyed talking with him. He was friendly and encouraging, and I simply felt good about the interview. The other interview was with Dr. Dorothy Ford, a specialist in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. She was able to question me intelligently and gracefully about my physical abilities and limitations. I was certain that she was not only interviewing me, but also assessing my handicap and the possibility that I might require what these days is called “accommodation.” I noted that both of my interviewers were married to physicians and I felt good about both interviews.

Then it was off for a walking tour of the medical school and the hospitals. The medical student leading the tour was a good ambassador for UVM: well - prepared, informative, friendly, talkative, and enthusiastic about the program and about the challenges. He walked at a fair pace, but did not hurry, and used the stairways but always asked if I would prefer to take the elevator and meet them on the next floor. I always said “no thanks, I’m fine” and I was. A year of weight training and crutching up twelve flights of stairs each day had worked some magic, so I was able to keep up with the “walkies” easily. I later wondered if the student guide kept track of my capabilities and reported back to the admissions committee. My wife Kathie says “definitely.” Just showing up shortly after the big snow didn’t hurt, either.

After the visit to UVM I drove back to college in Maine and resumed studies. Although I felt good about the visit I did not dare to be hopeful, but I was pleased that they had treated me cordially.

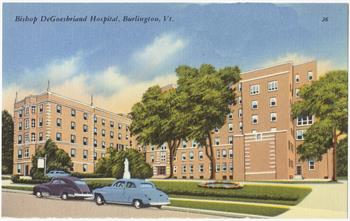

The DeGoesbriand

Most operating rooms are unpleasant work sites, large windowless rooms that are brightly lit with cold florescent lights and chilled to keep the gowned surgical team comfortable and to retard bacterial growth. A high capacity air conditioning system changes the air several times per hour, generating a constant low rumble that can make one sleepy. If a power failure occurs, within seconds emergency generators will restore it. Regardless of the weather outside or time of day the environment inside never changes. In many operating rooms it is possible to go to work in darkness and leave in darkness without seeing the outside world, especially during the winter months.

Most operating rooms are unpleasant work sites, large windowless rooms that are brightly lit with cold florescent lights and chilled to keep the gowned surgical team comfortable and to retard bacterial growth. A high capacity air conditioning system changes the air several times per hour, generating a constant low rumble that can make one sleepy. If a power failure occurs, within seconds emergency generators will restore it. Regardless of the weather outside or time of day the environment inside never changes. In many operating rooms it is possible to go to work in darkness and leave in darkness without seeing the outside world, especially during the winter months.

In contrast, the operating rooms in the old DeGoesbriand Unit were pleasant. The DU was a catholic hospital in Burlington that became part of the Medical Center Hospital of Vermont. The operating rooms, small by modern standards, were on the top floor and ample windows kept one connected with the outside world. Although most of the windows overlooked the parking lot or Pearl Street, those in the coffee break room offered a nice view of Lake Champlain and the Adirondack Mountains. There were four operating rooms and a cystoscopy room, all staffed by a close-knit group of nurses and technicians, and two orderlies; one of the orderlies, Gary Martin, became my favorite assistant. Sister Rock, perhaps the last remaining nun at the DU, occasionally helped out in the operating rooms. Rocky was quite a character, not a quiet, retiring, pious rosary - clutching nun. She was much like Sr. Mary Norberta, who I later met and worked with in Bangor. I sensed that both of these feisty, outwardly tough nun/nurses had a better grip on the realities of life than most people.

At the DU operating room suite I met Dick Pease, the anesthesiologist who introduced me to the specialty during my final year of medical school. He was in charge of anesthesia care at the DU and often hosted medical students who wanted experience in anesthesiology or emergency airway management. He asked me right upfront what I hoped to learn from a two - week stint, and delivered that and more. Dr. Pease had been a family doctor who had picked up added training and experience in anesthesia and joined the Medical Center staff. He was very businesslike and efficient, but he was also an excellent clinical instructor. He was the fastest by far at administering a spinal anesthetic, and it was a wonder to see how efficiently and painlessly he did it time after time. I watched and tried to emulate his technique and speed; and although I became very skilled, even after administering several thousand spinals I never could do it quite as nicely as he did. Dick was very goal oriented and he would do whatever was needed to finish the day’s work, often mopping the floor between cases. He had a large vegetable garden with which to feed his large family, and he occasionally brought in such treats as fresh rhubarb and asparagus. Occasionally the OR techs cooked up a special noontime meal for the staff in one of the autoclaves, an activity that surely would not be permitted today. There is no logical reason to forbid it because after all, an autoclave will sterilize whatever is properly processed in it, but perish the thought; the bureaucrats would never allow such activity. Official oversight and licensing is good when it protects the public from harm, but sometimes it merely stifles humanity and joy in the workplace. My experience at the DU, led by Dr. Pease and Dr. Roy Bell, a slightly dour Scotsman with a lovely sense of purpose and humor, was my best time in medical school. After providing some introductory hands on clinical instruction in general anesthesia Dr. Pease trusted me to watch over patients under anesthesia, never far away, but not hovering. I was hooked. I loved it.

He noted my interest and encouraged me to talk with Dr. Mazuzan, Chief of the Department, about becoming a resident. So I called Dr. Mazuzan and went up the hill to the big hospital, the Mary Fletcher Unit, to meet him. John Mazuzan was a local Burlington boy who made good, a sociable, talkative, and forthright man. He seemed to know all of the important anesthesiologists in the country on a first name basis and was politically savvy. Best of all, he was friendly and approachable. We talked, and then he offered to teach me how to administer a spinal anesthetic, as he had a case to do. With the patient lightly sedated, lying on his side and held in the fetal (curled up) position by one of the orderlies, I sat behind the patient with the spinal tray opened and ready, sterile gloves on, following instructions. Dr. Mazuzan stood over us both and told me how to prep the patient’s back with sterile Betadine solution. As I did this, the patient turned his head toward Dr. Mazuzan and said “Do you guys know what you’re doing?” Mazu didn’t hesitate a second. “Don’t you worry about a thing, between the two of us Dr. Sewall and I have done 10,000 of these.” Of course Dr. Mazuzan had done 9,999 and this was my first one… He was a great teacher, and his calm demeanor inspired confidence.

Dr. Mazuzan also shared Dr. Pease’s practical approach to getting things done, not hesitating to do tasks that many doctors think are beneath them. One evening when I was on emergency call with Dr. Mazuzan we waited for a patient to be brought to the OR by the ward nursing staff, but after twenty or thirty minutes we had no patient. Dr. Mazuzan said “C’mon, Doug, let’s go get the patient.” So the Chief of the Anesthesia Department and I took a gurney to the ward and brought our patient to the OR. This simple act taught me an important lesson: in patient care, no task should be beneath you whatever your title may be…do what needs to be done.

I was convinced that anesthesiology was what I wanted to do following medical school, but there was one problem: I had taken part in the national internship matching program and was slated to go to Hartford Connecticut for a one year internal medicine internship. I no longer wanted to do that because I had found the one niche in medicine that I truly enjoyed. Dr. Mazuzan offered to call the director of that program and explain my situation. I do not know the details of their conversation, but Dr. Mazuzan said that the other doctor was gracious and he relieved me of my obligation. I was “in.”

This was the best thing to happen to me in medical school. I thoroughly enjoyed anesthesiology and although the work was often tiring and challenging, it was also rewarding; Dr. Mazuzan was very good to me, as were many others in the department and in the operating rooms.

Clinical Medicine

Our introduction to clinical medicine began in the fall of the second year. We students first learned how to examine each other, starting with the basics such as how to use a stethoscope. After a couple weeks of instruction and classmate practice, one day I put on slacks, a clean dress shirt and necktie, and my new spotless white med student jacket, and with some trepidation went off to meet my first real hospital patient. I don’t remember the details, but am sure I was more nervous than the patient. During my medical school years I only remember one patient who surveyed me and said, “You look worse off than I am,” but many did ask me "what happened to you?" Generally the patients were very patient: back then they were interviewed and examined upon admission to the hospital by a nurse, a med student, a hospital intern, and sometimes by a hospital resident. All this before their own doctor appeared!

After interviewing and examining a patient, I would go to the nurses’ station, discuss the findings with the intern or with the resident, and write in the patient’s medical record my findings and a diagnosis and care plan. Longhand. One afternoon I interviewed and examined a middle - aged man who had lower back pain and leg pain. He was being admitted to hospital to have a myelogram (an X-ray study of his lower back, using radio-opaque dye injected into his spinal fluid). Such studies are now done on outpatient basis, (if at all, as most have been replaced with CT scans or MRI scans), but in 1972 it was customary to admit such patients to the hospital for at least one or two nights. I interviewed him, and during the physical exam I put him into several specific positions (studiously researched in a medical exam handbook beforehand) to learn what aggravated or relieved his symptoms. Then I went to the nurses’ station to write down my findings and to document a treatment plan. Soon he came padding down the hallway and said “Doc…I think you cured me. The pain is gone.”

He went home. I don’t know if I cured him or not, but if so, he was my first “cure” and I still don’t know how I did it.

As I progressed through various clinical rotations, things were not clicking for me. Surgery appealed to me, but was physically too difficult. The operating room head nurse at Mary Fletcher, Mrs. Raynelle Tucker, and her staff were wonderful, and helped find a way for me to safely scrub and gown for surgery, so I did assist at a few operations; but it was physically difficult, clearly not something I could do on a regular basis. Psychiatry would have been physically easy, and I liked and respected the chairman of the Psychiatry Department, but I could not understand what makes people tick...or not tick "normally."

Then I met Dr. Pease.